005*. Anna Ivanovna Vel'jaševa-Volynceva / Анна Ивановна Вельяшева-Волынцева

Anna

Ivanovna

Vel'jaševa-Volynceva,

next on our list,

was

born

in 1755. She thus belongs to an era subsequent to that of Mavra Šepeleva,

so

we'll flag her with an asterisk (*)

as

we take

this

opportunity to

indulge

in a

little

chronological

change of pace.

Anna

Ivanovna's

literary activity overlapped

with that of her sister Pelegeja

Ivanovna,

who

will

be the subject of our next post.

Golicyn

furnishes

two

distinct entries for Anna (46-47)

and

for

Pelegeja

(47),

without

explicitly

indicating

that

they were related, although

the

sisters’ unusual

last name and

matching

patronymics suggest a familial

connection

that

is borne

out in

other sources.

As

was the case

with most of the women writers who managed to publish their work in

eighteenth-century Russia,

the Vel'jaševa-Volynceva

sisters

belonged

to a literary family.

Their father,

notes

Golicyn,

was

a

"general

major of

the artillery and writer"

by the name of Ivan

Andreevič

Vel'jašev-Volyncev

(1737-1795).

More

specifically, he

was

a

respected

teacher of

"military

and mathematical sciences"

at

the Artillery

and

Engineering Cadet Corps in

Petersburg,

who

counted

future

field

marshal

Michail Kutuzov among

his students,

as well as author

of Russia’s

first artillery textbook (SPb.,

1767),

and the

translator

of

two

works by Voltaire

(1772,

1775)

and

Nollet's

Lessons

on Experimental Physics

(SPb.,

1779-81).

His

son Dmitrij Ivanovič

(1774

or 1775-1818)

was a military writer, too, who, after a brief,

but brilliant

military career – “at

25 he was already a colonel leading ponton companies”

(M.M. 869)

– went

on to compile

a

five-volume

Dictionary

of Mathematical and Military Sciences

(SPb., 1802).

Dmitrij's

deeper

interests

seemed

to be poetry

and drama, however:

he

translated

a

number of plays

and

other works

from

French and

German into

Russian throughout

his life, in

addition to authoring

his

own

verses and verse

fables;

from 1811, he

was

an active member of the Society

of

Amateurs

of Russian Literature (Общество

любителей российской

словесности)

at

Moscow University, whose boarding school he had attended as a boy.[1]

As

was the case

with most of the women writers who managed to publish their work in

eighteenth-century Russia,

the Vel'jaševa-Volynceva

sisters

belonged

to a literary family.

Their father,

notes

Golicyn,

was

a

"general

major of

the artillery and writer"

by the name of Ivan

Andreevič

Vel'jašev-Volyncev

(1737-1795).

More

specifically, he

was

a

respected

teacher of

"military

and mathematical sciences"

at

the Artillery

and

Engineering Cadet Corps in

Petersburg,

who

counted

future

field

marshal

Michail Kutuzov among

his students,

as well as author

of Russia’s

first artillery textbook (SPb.,

1767),

and the

translator

of

two

works by Voltaire

(1772,

1775)

and

Nollet's

Lessons

on Experimental Physics

(SPb.,

1779-81).

His

son Dmitrij Ivanovič

(1774

or 1775-1818)

was a military writer, too, who, after a brief,

but brilliant

military career – “at

25 he was already a colonel leading ponton companies”

(M.M. 869)

– went

on to compile

a

five-volume

Dictionary

of Mathematical and Military Sciences

(SPb., 1802).

Dmitrij's

deeper

interests

seemed

to be poetry

and drama, however:

he

translated

a

number of plays

and

other works

from

French and

German into

Russian throughout

his life, in

addition to authoring

his

own

verses and verse

fables;

from 1811, he

was

an active member of the Society

of

Amateurs

of Russian Literature (Общество

любителей российской

словесности)

at

Moscow University, whose boarding school he had attended as a boy.[1]

Dmitrij

began publishing at a tender age: if

his

first

poem was

printed

in 1789, when

he was about 18, his

first

theatrical

translation appeared

in

1782

– when he was roughly

11.

But it

was Anna,

and not Dmitrij, who was the family's literary trailblazer. Both Anna

and

Pelegaja began publishing translations at age 9.

Anna's first published translation even predates

her

father’s textbook

and in 1772,

when Dmitrij

would

have been roughly

a year

old,

she had

already earned an entry in N.

I. Novikov’s Attempt at a Historical Dictionary of Russian Writers

(Опыт

исторического словаря о российских

писателях,

SPb., 1772).

Describing

Anna as unmarried

and author

of "a fair

number of poems meriting praise",

Novikov wrote that she was also

to be commended

for

her translations "by

virtue of her

young age and assiduousness

(исправность)"

(29).[2]

What

exactly

did

Anna write? Golicyn

also

credits

her

with

the

composition of some verses,

together with three

book-length

prose

translations. We know very little about her

poetry,

however,

which,

like much of

women’s writing in the eighteenth century,

seems

to have been published

anonymously or under initials or pseudonyms.

M.

N. Makarov, who compiled a

list of

Russian women writers in 1830, averred

that

her

work was

"published

in many contemporary journals"

(34),

although specific titles are nowhere to be had.

Anna’s

verses –

or

perhaps

her

literary activity in general –

are

also

reputed

to have drawn

the

attention of Catherine

II,

which led

to her

being

presented at court

(M.M.

869) –

a

circumstance

that may

well have contributed

to

Anna's

enjoying

slightly

greater renown in

literary history than

her

sister Pelegeja.

Anna's

first translation

was taken

from the work of Madame

de Gomez (1684-1770),

a

popular

writer

of

exotic adventure

stories

and moralizing tales

who became quite fashionable in Russia in the 1760s. As a

nine-year-old, Anna was undoubtedly subject to some familial guidance

in the selection of her text,

which was published

in 1764

as О

графе Оксфортском

и

о миладии Гербии: Англинская повесть;

Сочинена г-жею Гомец

(On

the

Oxford Count and Milady Herby, an English Tale,

written by Mrs. Gomez)

(cfr.

Rosslyn 39); the

source text was Histoires

du comte d'Oxford,

de milady

d'Herby, d'Eustache de St-Pierre,

et de Béatrix

de Guinès

(Paris,

1737).

Anna's

first translation

was taken

from the work of Madame

de Gomez (1684-1770),

a

popular

writer

of

exotic adventure

stories

and moralizing tales

who became quite fashionable in Russia in the 1760s. As a

nine-year-old, Anna was undoubtedly subject to some familial guidance

in the selection of her text,

which was published

in 1764

as О

графе Оксфортском

и

о миладии Гербии: Англинская повесть;

Сочинена г-жею Гомец

(On

the

Oxford Count and Milady Herby, an English Tale,

written by Mrs. Gomez)

(cfr.

Rosslyn 39); the

source text was Histoires

du comte d'Oxford,

de milady

d'Herby, d'Eustache de St-Pierre,

et de Béatrix

de Guinès

(Paris,

1737).  The

support and involvement of Anna's

family is evident in the fact that her

book

was published by

the press

of

the Land

Forces Cadet

Corps

("тип.

Сухопут. кадет. корпуса"),

which was associated

with the

institution where her father taught, and even specifically at

his behest

("по

заказу майора Вельяшевa-Волынцева")

in a

sizable print run of 1200

copies

(Svodnyj katalog 1:246).

In

addition to putting Mrs. Gomez's name on the cover –

a

striking

choice in

this era of anonymity and one that suggests

the

marketing potential of the Gomez "brand" –

Anna's

editors

revealed her own identity as well, thus

making her

only

the

second woman in

Russian literary history to

attach

her name to a published

translation.

The first

had been the

princess

Daškova,

who just one year earlier had

issued a translation of two

pieces by Voltaire

(Rosslyn 1).

It

perhaps bears note that Daškova's

exalted social status often

safeguarded her

from

the repercussions of her

(often

unusual)

behavior,

while

Anna had no such protection from acts that might be judged as

overstepping appropriate gender roles.

The

support and involvement of Anna's

family is evident in the fact that her

book

was published by

the press

of

the Land

Forces Cadet

Corps

("тип.

Сухопут. кадет. корпуса"),

which was associated

with the

institution where her father taught, and even specifically at

his behest

("по

заказу майора Вельяшевa-Волынцева")

in a

sizable print run of 1200

copies

(Svodnyj katalog 1:246).

In

addition to putting Mrs. Gomez's name on the cover –

a

striking

choice in

this era of anonymity and one that suggests

the

marketing potential of the Gomez "brand" –

Anna's

editors

revealed her own identity as well, thus

making her

only

the

second woman in

Russian literary history to

attach

her name to a published

translation.

The first

had been the

princess

Daškova,

who just one year earlier had

issued a translation of two

pieces by Voltaire

(Rosslyn 1).

It

perhaps bears note that Daškova's

exalted social status often

safeguarded her

from

the repercussions of her

(often

unusual)

behavior,

while

Anna had no such protection from acts that might be judged as

overstepping appropriate gender roles.

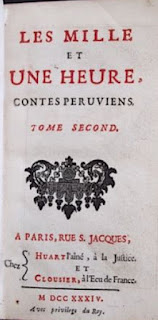

Anna

began her

second translation,

based on Gueulette's Les

Mille et Une Heures, contes peruviens

(1733, 1759),

at age ten. This

became

the two-volume

Тысяча

и один час, сказки перуанския

(A

Thousand and One Hours: Peruvian Fairy Tales),

printed

in

Moscow

(1766,

1767)

and capitalizing on

the rage for oriental exoticism created by Galland's Les

Mille et Une Nuits,

contes

arabes

(1703)

(Rosslyn 40-41).

A

third volume of translation added to these in 1778 appears to have

been the work of another translator designed to profit from the

foundation laid by Anna (Rosslyn 146,

Svodnyj

katalog 1:210).

Her

third

translation,

which appeared in Moscow in

1770,

brought

Russian

readers a text that

Frederick the Great had written

(in

French)

as

История

Бранденбургская, с тремя разсуждениями

о нравах, обычаях и успехах человеческого

разума, о суеверии, законе, о причинах

установления или уничтожения законов,

короля Прусского Фридриха II

(The

Brandenburg History with Three Reflections on the Morals, Customs and

Successes of Human Reason, on Superstition, Law, and the Motives for

the Imposition or Abolition

of Laws by the King of Prussia, Frederick II).

This

translation attracted

Catherine's

attention

as

well. According

to

an

anecdote

she

took

this opportunity to crow to Diderot,

"Now

in Russia we've

translated Frederick! And who do you think did it? A young, pretty

girl!"

"Your

Highness,"

Diderot

conceded,

"in

your

Russia

and under your rule

one finds all the wonders of the world, while in Paris very few men

even read

Frederick"

(Makarov 34-35).

Anna

Vel'jaševa-Volynceva

seems to have stopped translating after Frederick, "perhaps,"

as Wendy Rosslyn suggests, "because by 1770 she had

reached

marriageable age"; of her husband, we know only that his surname

was Olsuf'ev

(42, 175).

Anna

Vel'jaševa-Volynceva

seems to have stopped translating after Frederick, "perhaps,"

as Wendy Rosslyn suggests, "because by 1770 she had

reached

marriageable age"; of her husband, we know only that his surname

was Olsuf'ev

(42, 175).What might students do with Anna Ivanovna Vel'jaševa-Volynceva? It is unlikely that we can track down her poems, but one could certainly investigate their context a bit further. What journals might have printed them in, say, the 1760s or 1770s? What were the leading journals of that era and what kinds of signatures are attached (or missing) from the verses printed in them? And what about her translations? Where can they be found today and how might they offer material on the principles of the translator's art as she understood it?

FURTHER

READING:

M. M. [M. N. Mazaev]. "Anna Ivanovna Vel'jaševa-Volynceva", in Encyclopedičeskij slovar' Brokgauza i Efrona, vol. 5A (SPb.: Semёnovskaja Tipografija, 1892), 869.

Makarov, M. N. "Anna Ivanovna Vel’jaševa-Volynceva", in "Materialy dlja istorii ruskich ženščin-avtorov." In Damskij žurnal (1830), no. 3, ch. 29, 34-35.

Novikov, N. I. Opyt istoričeskogo slovarja o Rossijskich pisateljach. SPb.:1772.

Rosslyn, Wendy. Feats of Agreeable Usefulness: Translations by Russian Women 1763-1825. FrauenLiteraturGeschichte 13. Fichtenwalde: Verlag F. K. Goepfert, 2000.

On Ivan Andreevič and Dmitrij Ivanovič Vel'jašev-Volyncev

Encyclopedičeskij slovar' Brokgauza i Efrona, vol. 5A (SPb.: Semёnovskaja Tipografija, 1892), 869.

Enciklopedičeskij leksikon, vol. 9 (SPb: Tipografija V. Pljušaraj, 1837). 337-38.

Ravdin, B. N. and A. B. Roginskij, "Dmitrij Ivanovič Vel'jašev-Volyncev." In Slovar' russkich pisatelej XVIII veka, vyp. 1 (L., 1988).

Slovar’ členov Obščestva ljubitelej Rossijskoj Slovesnosti pri Moskovskom Universitete (М.: Pečatnja A. Snegirevoj, 1911), 52-53.

Svodnyj katalog russkoj knigi graždanskoj pečati XVIII veka, 1725-1800 (M.: Izd. Gos. Biblioteki SSSR im. Lenina, 1962-1964), vol. 1, 210, 246; vol. 2, 177.

Zaborov, P. R. "Ivan Andreevič Vel'jašev-Volyncev." In Slovar' russkich pisatelej XVIII veka, vyp. 1 (L., 1988).

NOTES:

[1] For more information on Ivan and Dmitrij Vel'jašev-Volyncev, see "Further Reading" above.

[2] Novikov's Dictionary, one of the first reference works of its kind in Russia, contains nine women writers: E. V. Cheraskova, M. V. Chrapovitskaja, E. R. Daškova, M. V. Zubova, E. A. Knjažnina, A. F. Rževskaja, N. I. Titova, E. S. Urusova, and A. I. Vel'jaševa-Volynceva.

M. M. [M. N. Mazaev]. "Anna Ivanovna Vel'jaševa-Volynceva", in Encyclopedičeskij slovar' Brokgauza i Efrona, vol. 5A (SPb.: Semёnovskaja Tipografija, 1892), 869.

Makarov, M. N. "Anna Ivanovna Vel’jaševa-Volynceva", in "Materialy dlja istorii ruskich ženščin-avtorov." In Damskij žurnal (1830), no. 3, ch. 29, 34-35.

Novikov, N. I. Opyt istoričeskogo slovarja o Rossijskich pisateljach. SPb.:1772.

Rosslyn, Wendy. Feats of Agreeable Usefulness: Translations by Russian Women 1763-1825. FrauenLiteraturGeschichte 13. Fichtenwalde: Verlag F. K. Goepfert, 2000.

On Ivan Andreevič and Dmitrij Ivanovič Vel'jašev-Volyncev

Encyclopedičeskij slovar' Brokgauza i Efrona, vol. 5A (SPb.: Semёnovskaja Tipografija, 1892), 869.

Enciklopedičeskij leksikon, vol. 9 (SPb: Tipografija V. Pljušaraj, 1837). 337-38.

Ravdin, B. N. and A. B. Roginskij, "Dmitrij Ivanovič Vel'jašev-Volyncev." In Slovar' russkich pisatelej XVIII veka, vyp. 1 (L., 1988).

Slovar’ členov Obščestva ljubitelej Rossijskoj Slovesnosti pri Moskovskom Universitete (М.: Pečatnja A. Snegirevoj, 1911), 52-53.

Svodnyj katalog russkoj knigi graždanskoj pečati XVIII veka, 1725-1800 (M.: Izd. Gos. Biblioteki SSSR im. Lenina, 1962-1964), vol. 1, 210, 246; vol. 2, 177.

Zaborov, P. R. "Ivan Andreevič Vel'jašev-Volyncev." In Slovar' russkich pisatelej XVIII veka, vyp. 1 (L., 1988).

NOTES:

[1] For more information on Ivan and Dmitrij Vel'jašev-Volyncev, see "Further Reading" above.

[2] Novikov's Dictionary, one of the first reference works of its kind in Russia, contains nine women writers: E. V. Cheraskova, M. V. Chrapovitskaja, E. R. Daškova, M. V. Zubova, E. A. Knjažnina, A. F. Rževskaja, N. I. Titova, E. S. Urusova, and A. I. Vel'jaševa-Volynceva.

ILLUSTRATIONS:

1, 2, 4. Title page and illustrations by Gunt from Gueullette's Les mille et une heures (Paris, 1734) from a book dealer's site.

5, 6. Engraving by G. F. Schmidt from Frederick's Memoires pour servir a l'histoire de la maison de Brandebourg (1751).

1, 2, 4. Title page and illustrations by Gunt from Gueullette's Les mille et une heures (Paris, 1734) from a book dealer's site.

5, 6. Engraving by G. F. Schmidt from Frederick's Memoires pour servir a l'histoire de la maison de Brandebourg (1751).

Comments

Post a Comment